Confronting Water Scarcity: New Mexico's Dual River Crisis

Written on

Chapter 1: The Water Crisis Unfolds

New Mexico is grappling with severe water shortages, an issue that has reached alarming levels. As I journeyed through the Southwest and witnessed the catastrophic impacts of a prolonged megadrought, I documented various stories that resonated with many. This particular narrative gained the most attention.

This state, my chosen home, is experiencing water scarcity like never before, which is evident even in my own neighborhood. Having moved from Chicago, where the presence of Lake Michigan makes water seem abundant, the contrast is striking. In New Mexico, if it were recognized as a separate nation, it would rank among the top ten or eleven in terms of water deficiency. The region has endured over two decades of drought, with no signs of improvement; rainfall patterns have drastically shifted.

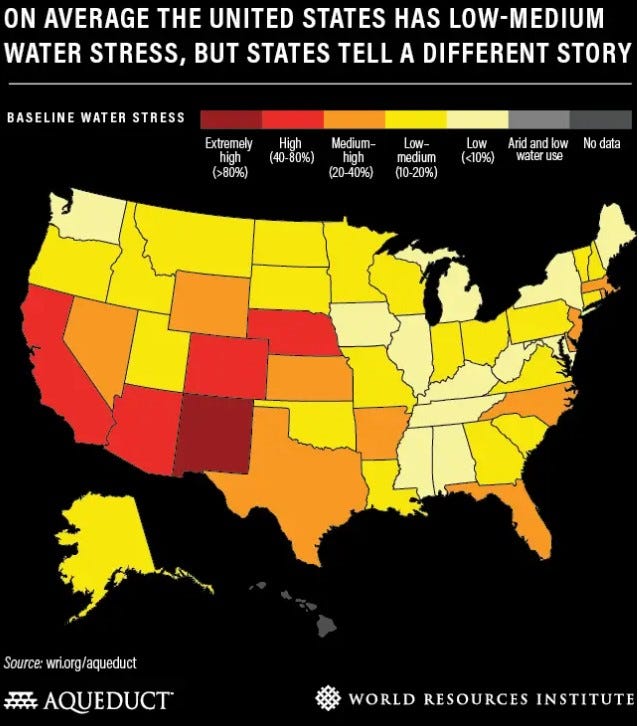

The World Resources Institute reported that, by 2019, New Mexico exhibited the highest water stress of any state in the U.S. Our relatively slow growth rate of about 3% offers some relief, as only Wyoming has a slower pace of development. In contrast, neighboring thirsty states like Utah, Arizona, and Nevada have growth rates exceeding 10%, worsening the already desperate situation in the Colorado River basin.

Currently, the state legislature appears unfazed, convening for only thirty days in even-numbered years. This year’s limited agenda largely focuses on areas like education and law enforcement, with little attention paid to the pressing water crisis.

Chapter 2: The Essential Need for Water

At the foundation of Maslow’s hierarchy lies our physiological needs, encompassing air, food, and water. Given that water is crucial for food production, it stands as a primary necessity. Eastern New Mexico, part of the High Plains, relies heavily on the Ogallala Aquifer—America’s largest aquifer—to support its agricultural and ranching activities. This vital resource also nourishes vast areas across Nebraska, South Dakota, Wyoming, Colorado, Kansas, Texas, and Oklahoma. However, over-extraction has led to a decline in the aquifer's levels, with agriculture consuming up to 83% of the water drawn.

While New Mexico boasts a strong agricultural sector, ranchers are struggling due to insufficient forage, forcing them to reduce their herds and purchase costly hay. Many are now seeking federal assistance to mitigate their financial losses, with approximately 44% of the state's agricultural income generated from cattle.

As rancher Cassidy Johnston poignantly remarked in The New Humanitarian, “We count on rain. We count on rain for everything.” The competition for water resources now extends to pecan and pistachio orchards, the thriving chile industry, and even the burgeoning recreational marijuana sector.

Chapter 3: The Rio Grande and Pecos River

The Rio Grande flows through New Mexico from north to south, dividing the state. Nearly 80% of the river’s water is allocated to agriculture, while also serving urban areas like Albuquerque and El Paso, as well as Ciudad Juarez across the border. Unfortunately, the river often runs dry in Southern New Mexico, rejuvenated only by aquifers.

Water distribution to New Mexico and Texas is governed by the 1938 Rio Grande Compact, which originated from the river's source in Colorado. A previous treaty from 1906 established how much water would be allocated to Mexico. Presently, a legal dispute is ongoing in the Supreme Court, with Texas accusing New Mexico of not adhering to the agreements. Conversely, New Mexico contends that it is not receiving its fair share, relying instead on groundwater for sustenance. The U.S. Department of Justice has sided with Texas in this matter.

The Pecos River, originating near Las Vegas and flowing through eastern New Mexico, faces its own challenges. Despite a series of dams that help conserve water, the smaller populations reliant on this river offer a glimmer of hope. However, Texas has historically asserted its dominance, filing lawsuits against New Mexico in 1949 and 1974 over water rights and groundwater depletion issues, with the Supreme Court ruling against New Mexico in 1983.

In the southeastern region, the Pecos traverses the oil-rich Permian Basin, where water is also essential for fracking operations. With New Mexico already in arrears to Texas, the latter is drawing from a shared aquifer to compensate.

Chapter 4: A Call to Action

The crux of the water crisis is the ongoing lack of precipitation in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico. Following a lackluster monsoon season in 2021, rainfall levels have remained below normal, compounded by higher temperatures and a relentless 22-year drought. The forecast indicates more of the same.

Albuquerque could benefit from launching a water awareness initiative and imposing restrictions; however, it already ranks among the lowest cities in the West for water usage, averaging 121 gallons per household daily. El Paso is set to implement water restrictions starting April 1.

As Rolf Schmidt-Petersen, director of the Interstate Stream Commission, stated, “There’s no water in the bank, so to speak, next year.” The future of New Mexico’s water resources hangs in the balance, prompting the caution not to chase waterfalls—what few remain may soon be memories.

The first video, Tale of Two Rivers, explores the intricate relationship between the Rio Grande and Pecos Rivers, highlighting the challenges they face due to water scarcity.

The second video, CH5 - Nature Documentary - Paradise in Peril: River of Sand (1998), delves into the environmental issues surrounding river systems, providing a broader context to the ongoing water crisis.

Sources for this article include: