A Reflection on the Apollo Program: A Vision of What Could Have Been

Written on

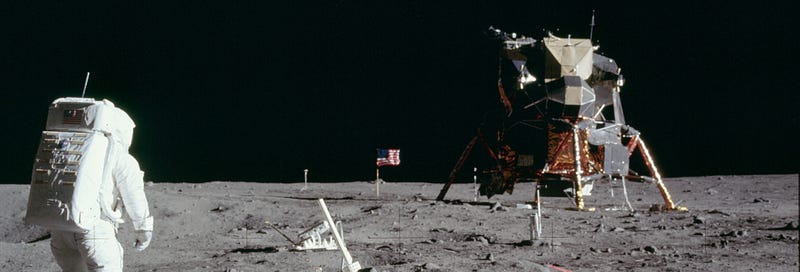

This year commemorates half a century since humanity's first crewed lunar landing. Amidst the celebrations—documentaries, parades, speeches, and events—we are likely to witness a reassessment of the significance of Apollo. Such reexaminations accompany major anniversaries and often stir debate. For instance, the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was particularly contentious, while ANZAC Day each year brings its own reinterpretations as part of remembrance. Notably, my research into labor has illuminated how spaceflight—especially Apollo—has been perceived. Pondering "What does spaceflight signify?" is especially pertinent today and yields unexpected insights.

Historical Memory

In my previous role as a lecturer in American History, I structured my curriculum around three central themes, one being the concept of historical memory. I drew inspiration from David Blight's analysis of the "Lost Cause" narrative in the American South and Richard White's examination of the American Frontier. White discussed the contrasting portrayals of the frontier by Buffalo Bill and Frederick Jackson Turner during the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition. Turner, the more serious historian, crafted a narrative suggesting that the trials of the frontier stripped immigrants of their identities, allowing them to forge new American identities through hard work. Conversely, Buffalo Bill depicted a more violent tale of settlers defending themselves from Indigenous peoples in fierce confrontations.

Both narratives showcase rugged individualism, yet Turner focuses on pioneers and cabins, while Buffalo Bill centers on soldiers and conflict. As White notes, while these accounts seem to represent fact versus fiction, over the past century, they have blended into a coherent narrative that shapes our contemporary discussions about cowboys and Native Americans. He asserts:

> "These narratives about the West hold significance. They not only reflect our self-perception but also influence our interactions with one another. ... The tales [Turner and Bill] spun were not purely invented but rather selective retellings of history, with authors omitting elements that didn’t align with their narratives. This selectivity was essential, as the past itself is not a narrative; it serves as raw material for coherent stories, not all of which are factual."

I often reminded my students that this selectivity encompasses both inclusion and omission.

The Final Frontier

In my survey course, I allowed students to propose their essay topics, and one suggestion was the Apollo landings. Unfortunately, this proved inadequate; through grading numerous subpar essays over four years, I found a scarcity of quality historical scholarship on the space program. I had hoped students who grasped the concept of historical memory would seize the chance to analyze films alongside primary sources like newspapers and broadcasts. Instead, I received essays laden with technical jargon, recycling the notion that NASA’s achievements were both a moment of global unity and a testament to American superiority—especially over the Soviets. My students seemed resistant to recognizing that these narratives of technological prowess and national pride were the very historical memories I wanted them to explore.

Film has served as a significant medium for historical interpretation, particularly over the last century. Since the 1980s, portrayals of the U.S. space program have evolved considerably. In The Right Stuff, produced during the ultra-capitalist 1980s, astronauts were depicted as frontiersmen, characterized by an all-American spirit and rugged individualism. After all, space represents the ultimate frontier, and the ill-fated Firefly illustrates the connection between the West and outer space. In the 1990s, Apollo 13 transformed astronauts into icons of national resilience amidst crisis, showcasing a narrative of collective effort rather than individual bravado. The 2010s brought about Hidden Figures, which valiantly reintroduced the contributions of Black women to the Mercury program, while First Man offered a glimpse into the sacrifices made by astronauts’ spouses. This era also depicted white male astronauts as emotionally stunted, contrasting sharply with the cowboy imagery of the 1980s and the patriotic fervor of the 1990s.

As White noted regarding the frontier, there’s an element of truth in all these narratives. The Black women who served as 'human computers' in the Mercury program were real figures, unjustly erased from the tale of white ingenuity and technical excellence. Astronauts did embody cowboy characteristics at times. In the documentary Last Man on the Moon, Eugene Cernan is seen at a rodeo, and he acknowledges the neglect faced by Apollo astronauts' wives, who lived in gated military communities. First Man utilizes archival footage and a rendition of Gil Scott-Heron's "Whitey on the Moon" to highlight contemporary discontent with the perceived misallocation of public funds on Saturn Vs while people suffered on Earth. Additionally, the collaborative spirit showcased in Apollo 13 echoes Michael Collins' own reflections on the Apollo missions:

> "... The Saturn V rocket that launched us into orbit is an incredibly intricate machine, each component functioning flawlessly ... Our confidence in this equipment is unwavering. This success is the culmination of the hard work of countless individuals ... While only three of us are visible, beneath the surface are thousands more, to whom I extend my gratitude."

The Saturn V serves as a powerful symbol of collective effort toward a shared objective, with the small command module housing the astronauts representing merely the tip of a vast spear, supported by generations of scientists and engineers. This is why many scholars engaged with labor or collective endeavors reference the space program, especially Apollo.

Utopian Dreams of Freedom

Hannah Arendt deemed Sputnik an event of unparalleled significance, rivaling even the splitting of the atom. However, the liberation that Sputnik symbolized extended beyond gravity:

> "... Interestingly, this joy was not one of triumph; it was not a celebration of human power and mastery, but rather a relief at taking the first step away from humanity's confinement to the earth. This sentiment, far from being a mere oversight by an American journalist, echoed a profound sentiment inscribed on the obelisk for a prominent Russian scientist: 'Mankind will not remain bound to the earth forever.'"

The language used here evokes themes of imprisonment and bondage, suggesting their opposite, freedom. These themes recur in scholarly discussions surrounding labor. Tom Hodgkinson explicitly states: "space represented the ideal of freedom." Similarly, Asif Siddiqi discusses Soviet aspirations in space exploration, promising "complete liberation from the burdens of the past: social injustice, imperfection, gravity, and ultimately, Earth." He recounts a riot that erupted in 1924 when rumors of a potential Soviet moonshot circulated. Snricek and Williams interpret Siddiqi's findings to illustrate that "one of the most pervasive and subtle aspects of hegemony is the limitations it imposes upon our collective imagination." If space travel in the 1960s made the impossible seem attainable, its absence today constrains our horizons, rendering what once felt feasible as insurmountable.

In The Utopia of Rules, David Graeber describes the motivations behind Apollo as a "mythic vision," lamenting the current lack of such aspirations. However, he also emphasizes that it was a "quintessential Big Government project," contending, alongside Perelman and Mazzucato, that the private sector generally lacks the capacity to yield innovations of comparable scale and impact to those stemming from public research funding.

Oli Mould aligns with Graeber in Against Creativity, citing JFK's address to Congress on May 25, 1961, as a commitment to "achieve the impossible." Mould argues that the public nature of the moon mission distinguished it: "It was a global triumph of collective creativity, propelling humanity forward in its quest for civilization. It was the manifestation of a shared belief in, and realization of, an impossible dream." However, he cautions that "perhaps it was the last." He observes that "many of humanity's most ambitious ideas have now been co-opted by capital ... Creativity has been privatized."

Similar to Snricek and Williams, Graeber and Mould view Apollo as indicative of a troubling shift in our historical trajectory since the 1970s. Graeber notes that while space exploration advanced from suborbital flights to lunar missions, it subsequently regressed to a deteriorating low Earth orbit station. Likewise, the sense of possibility that propelled aviation from the DC-3 to Concorde has dissipated, leaving travelers confined to cramped and uncomfortable mass transit, restricted by the speed of sound. Mould highlights that innovation no longer aims at equitable or practical ends: "any significant advancements we achieve are dictated by private interests." The declining focus on faster aircraft, while "innovation" concentrates on cramming more passengers into existing designs to boost airline profits, reflects the priorities of profit-driven motivations.

Hodgkinson notes the prevalence of language today that frames aspirations of reaching for the stars as folly, promoting resignation to the market's demands as wise:

> "Yet, our practical-minded leaders perceive looking skyward as a waste of time. Our very language valorizes being earthbound, deriding those with loftier ambitions. Negative terms abound: head in the clouds, starry-eyed, losing grip, not living in the real world, moon-faced loon, lunatic, airy-fairy, space cadet, away with the fairies, moonstruck, on another planet. Conversely, positive terms include: feet on the ground, anchored, down-to-earth, grounded, keeping your head down, getting a grip."

The rise of economy seating serves as a fitting metaphor for the shared concerns of these authors: at some point, society ceased to dream of impossible endeavors—initiated, as Kennedy suggested, precisely because they are challenging—and instead lowered expectations to merely extracting the last drops of efficiency from existing technologies.

These scholars converge on the sentiment that Apollo made a Utopian future seem just within reach. Hodgkinson encapsulates this notion:

> "Humanity yearns to soar, to commune with the divine, to ascend to godhood. The NASA moon landings served as the most spectacular testament to this ambition. Despite the clinical scientific approach and practicality of these lunar missions, the wonder, mystery, and enchantment remained intact. Space, indeed, has become the latest battleground in the age-old conflict between materialists and mystics."

Slipping the Surly Bonds of Work

The concept of liberation from labor prominently features in the writings of white male scholars on the future of work; thus, the metaphor of liberation from gravity resonates strongly. It is essential to recognize that zero gravity can be uncomfortable and burdensome to the body. Interestingly, the sole woman referenced here, Arendt, firmly believed that genuine freedom from toil is unattainable: she viewed labor as a perpetual struggle against growth and decay. The men in this discourse rarely acknowledge that some tasks, like taking out the trash, will always need doing; they merely wish for such chores to be managed. Their perception of constraints as intolerable may stem from a unique historical privilege.

At Apollo’s 50th Anniversary, I anticipate that individuals will connect with the moon landings for various reasons, all grounded in contemporary realities rather than historical nostalgia. For me, this connection appears as follows: we inhabit a work environment where individuals in first-world office settings strive to derive meaning from their jobs; where every employee is a project manager, each role demands 'soft skills' such as 'stakeholder management' and 'influencing without authority,' and where desired outcomes are articulated so poorly that we require an array of cumbersome, proliferating acronyms (are they now SMART, SMARTTA, or ISMART goals?). In this context, Apollo represents the elusive ideal: meaningful work that employs the expertise one has painstakingly developed, directed toward a clearly defined objective, with transparent success and failure metrics. Given our current climate, where collective action feels nearly impossible and the market's profit motives dominate, we need the Apollo narrative as an emblem of grand-scale collaboration.

This post was originally published on my blog.