Transforming Opioid Withdrawal Treatment for Newborns

Written on

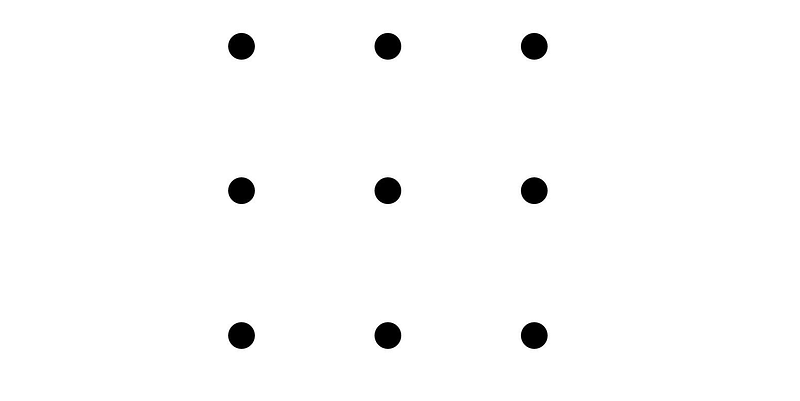

This narrative begins with a challenge. Can you break free from conventional thinking? Consider this nine-dot puzzle printed on paper. Your task is to connect all the dots using just four straight lines, without lifting your pen from the page.

We'll return to this puzzle soon, but first, let's reflect on the past.

An Expected Assembly

Five years prior, I found myself entering a San Diego convention hall, arriving ten minutes early for a presentation, yet struggling to find an empty seat. Physicians from across the nation had gathered to hear from experts discussing the latest findings and trends in the care of hospitalized patients. I was not alone in my interest in the session titled “Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome: Rethinking Our Approach.”

Neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), also known as neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS), affects infants born to mothers who have used opioid substances such as heroin, morphine, hydrocodone, and methadone. These drugs cross the placenta during pregnancy, infiltrate the developing fetus's brain, and lead to withdrawal symptoms upon birth as infants lose access to the opioids they had become accustomed to in utero.

The Weight of the Condition

The opioid crisis over the last thirty years has led to a steady rise in NAS cases among newborns in the U.S. It is estimated that up to 2% of infants born in hospitals develop NAS, with a new diagnosis occurring roughly every 15 minutes. A study in the New England Journal of Medicine indicated that from 2004 to 2013, the share of NICU days attributed to NAS grew from 0.6% to 4%.

NAS places a heavy financial burden on healthcare systems and families alike. By 2014, the cost to taxpayers through public insurance exceeded $400 million annually. Research conducted across 23 hospitals revealed that, from 2013 to 2016, infants with NAS spent an average of 19 days in the hospital at a cost of about $37,584 each, compared to three days and $3,536 for newborns with other medical issues.

In addition to financial stress, NAS impacts the emotional well-being of infants and their caregivers, especially mothers. The opioid spectrum ranges from illegal drugs like heroin to prescribed pain relievers and addiction treatment medications. A pregnant woman might take opioids for various reasons, which does not necessarily indicate a disregard for her unborn child.

A Loud Awakening

Let’s rewind to 2011 when I was in my first year of residency and rotating in the NICU. I vividly recall hearing the sharp cry of a newborn suffering from NAS for the first time. These infants may be inconsolable and exhibit a range of symptoms, including heightened startle reflex, increased muscle tone, poor feeding, frequent sneezing, and even seizures.

At that time, the prevailing treatment for NAS involved administering opioid medications—typically morphine or methadone orally. The rationale was to alleviate withdrawal symptoms by replacing the opioids that babies were no longer receiving from their mothers, gradually tapering the pharmaceutical dose until the infant was completely weaned off.

Similar to veterinary practices, the inability of infants to communicate their feelings complicates treatment. To assess the severity of withdrawal, symptom-based scoring systems were developed. Given the wide array of NAS-related symptoms, these scoring methods became quite intricate.

The Birth of a System

Introduced in 1975, the Finnegan Neonatal Abstinence Scoring System (FNASS), named after Dr. Loretta Finnegan, quickly became the standard for evaluating NAS. My hospital employed this 21-point scoring system in 2011, assessing infants every three hours based on various NAS-related factors, including sleep duration, presence of tremors, feeding difficulties, and irritability.

Protocols based on FNASS scores were established to guide adjustments in medication dosages. My hospital took pride in implementing the latest protocols to enhance the comfort of these infants and minimize their hospital stays.

Despite efforts to streamline this process, it was not uncommon for me to care for an infant for over 20 days. I often received late-night calls to increase a baby’s methadone dose due to a higher Finnegan score, sometimes triggered by a single yawn or sneeze.

Families were often devastated to learn that their infant would not be going home for another few days due to protocol adjustments. Like many of my peers, I began to question whether there might be a more effective way to care for these vulnerable infants and their families.

Identifying the Flaws

I started noticing inconsistencies in the scoring system. I observed sudden fluctuations in Finnegan scores coinciding with nursing shift changes. These changes appeared to stem from a subjective and variable assessment process. For instance, distinguishing between mild and moderate tremors could be challenging.

Another limitation of FNASS was its lack of specificity. While babies with NAS might frequently yawn, sneeze, or tremble, these symptoms were not exclusive to NAS.

Despite believing we were using the most current and evidence-based practices, I began to realize that the system required not just improvement, but a complete overhaul.

A Vital Revelation

Fast forward to 2016: in that packed conference hall, Dr. Matthew Grossman, a pediatric hospitalist from Yale New Haven Children’s Hospital, presented his insights. Initially following traditional methods similar to my training, Grossman began making changes after a few years.

His presentation captivated the audience of healthcare professionals. He posed a fundamental question: why were we adhering to these methods? The answer seemed to be that we were merely following established practices. He likened this to adding sails to a boat; the real solution lay in changing the mode of propulsion.

A Fresh Perspective

Grossman and his Yale team proposed a straightforward framework: infants need to eat, sleep, and be comforted (ESC). These three fundamental needs were easily measurable and were prioritized above all else. Medication was only provided if these basic needs could not be met.

The ESC model transformed both assessment and treatment. Rather than adhering to a strict schedule for opiate weaning, morphine was administered on an as-needed basis, meaning a dose did not signify regression in the weaning process.

Furthermore, instead of isolating infants in the NICU, they remained with their mothers in the mother-baby unit, emphasizing family involvement. Comforting practices such as breastfeeding, skin-to-skin contact, and creating a calming environment became the norm.

Grossman shared his remarkable results: over two years, the average hospital stay for 287 NAS patients decreased from 22 to just 6 days. Morphine use plummeted from 98% to 14%, and the average cost of care dropped from $44,824 to $10,289, with no negative outcomes recorded.

Sharing the Knowledge

Upon returning home from the conference, I was eager to implement the ESC model at my hospital in Montana. Fortunately, my colleague, Dr. Allison Rentz, a neonatologist, was also inspired and led our hospital to adopt ESC the following year. Rentz noted the significant positive impact of Grossman’s approach: “The reduction in length of stay and morphine use was evident everywhere it was applied—no negatives.”

Our facility has a volunteer cuddler program for infants with NAS who lack family members to provide comfort. Although this program was paused during the Covid-19 pandemic, prior to that, over 400 applicants vied for just 30 positions.

The ESC model has rapidly spread to hospitals nationwide. The Yale team's protocol was replicated by Boston Medical Center, which then shared a toolkit with the Colorado Perinatal Care Quality Collaborative and beyond. Rentz mentioned, “We had educational materials and templates ready to go, which typically takes longer to develop in a small state like this.”

Demonstrable Success

Before adopting ESC, our hospital had managed to reduce the average length of stay for NAS patients to about 12 days using previous improvement methods. However, with ESC, that number plummeted to just four to five days.

Other institutions reported similar successes. Boston Medical Center experienced a 35% reduction in length of stay and a 54% decrease in the use of medications, while the University of North Carolina's health system saw a 52% reduction in length of stay and a 79% drop in pharmacotherapy. ESC principles have now been applied in at least 25 states, with more joining the movement.

The Nine Dots Puzzle

The development and dissemination of the ESC model exemplify the innovative problem-solving approach championed by Dr. Grossman. Reflecting on the earlier puzzle, it becomes clear that solving it requires one to think beyond conventional boundaries. As Grossman pointed out in a 2019 article for Hospital Pediatrics, one must realize there is no box at all.

In dealing with NAS, healthcare providers had inadvertently confined themselves to traditional practices. We followed established methods simply because they were the norm. Eventually, someone recognized that these limitations were unnecessary. This realization prompted Grossman to explore how this principle could apply to other areas within pediatric medicine.

He noted, “Boxes exist throughout medicine. For instance, neonatal jaundice is commonly treated with phototherapy, despite elevated bilirubin levels being a normal occurrence in newborns.” He emphasized the need to treat pathological jaundice while recognizing that we often medicalize natural processes.

I posed a similar question to Rentz, who identified a box surrounding nasogastric (NG) feeding. Many premature infants struggle with the ability to suck and swallow, necessitating NG tube placement for nutrition. Rentz highlighted a growing trend to develop home NG programs, enabling parents to provide necessary feeding while reducing hospital stays.

Physicians pledge to do no harm, often erring on the side of caution, especially with the youngest patients. I hope that as medical knowledge advances, clearer guidelines will emerge regarding when conditions like NAS, neonatal jaundice, or dysphagia warrant aggressive intervention versus when they can be allowed to progress naturally with minimal interference.