Exploring the Contrast of Dark Dynamics and Bright Stability in Avian Species

Written on

In the animal kingdom, a consistent sensory inclination leads to a striking phenomenon where the more visually dynamic body parts of creatures often appear darker, while their comparatively static regions are depicted in brighter hues.

> “Thus everyone would likely concur with Lipps, asserting that pure yellow embodies happiness, deep blue signifies calm seriousness, red conveys passion, and violet evokes a sense of longing; orange merges the joy of yellow with the fervor of red, while green combines the brightness of yellow with the tranquility of blue. In essence, brighter and warmer tones are uplifting and stimulating, whereas darker and cooler tones are more introspective and restful.” > — Dewitt H. Parker, The Principles of Aesthetics (1920)

Topics

- Marvelous Spatuletails

- Vogelkop Superb Birds of Paradise

- Western Parotias

- Red-Capped Manakins

- Flame Bowerbirds

- General Bird Coloration

- Rainbow Coloration in Birds

- Bird Coloration by Taxa

- Butterflies

- Mammals

- Dark — Dynamic Bias

- More and Less Excitement

- Psychological Duality

- Random Bird Sample Data (For Reference)

- Works Cited

Marvelous Spatuletails

The marvelous spatuletail (Loddigesia mirabilis), an endangered hummingbird native to Peru, performs a captivating dance by alternating his head's position to showcase either the purple on the crown or the green on his neck, depending on his speed. This bird oscillates between stillness and swift lateral movements. During moments of stillness, he tilts his head back, allowing the female to observe the green hue. In contrast, during rapid movements, he lowers his head to reveal the purple. His display aligns the green with stillness and the purple with motion.

The coloration of the spatuletail and similar hummingbirds usually features darker shades—like black, blue, or purple—on their dynamic body parts such as wings and tails, while their less mobile areas like the breast, belly, and genital regions exhibit brighter colors like white, red, orange, or yellow. This overall pattern of dynamic darkness coupled with bright stasis can be traced back to the same inclination that prompts the spatuletail to switch from green to purple during its dance.

Assuming that white correlates with the brighter end of the color spectrum and black with the darker end, it appears that most birds, and likely many animals, are colored in a manner where their more outward, flowing, and dynamic parts are darker compared to their central and stationary sections.

If animals tend to prefer darker, cooler colors during movement and brighter, warmer colors during stillness, we should observe this blend in the elaborate courtship dances of various species. This exploration of how different species mix light and motion during mating displays could unveil countless examples of animals transforming dynamically, as seen with the marvelous spatuletail, showcasing darkness in movement and brightness in stasis.

Vogelkop Superb Birds of Paradise

The interplay of dark dynamics and bright stasis is crucial in the performance of the Vogelkop superb bird-of-paradise (Lophorina niedda). In its dance, the dark body parts, including wings and tail, undergo remarkable transformations in shape. These elements are raised and lowered, slapped against surfaces, and shaken, exhibiting far more dynamic movement compared to the consistently bright, blue, mouth-like invitation on its chest, which remains steady throughout the performance.

Western Parotias

The western parotia (Parotia sefilata) presents a striking display, characterized by a deep black ballerina skirt, which is showcased from above by the female during the latter part of the dance. He appears to spin and sway in a way reminiscent of a top nearing instability. He features several circular tufts at the tips of bare wires protruding from his head that move in various patterns around the skirt's edge. Following this intense movement, he halts, maintaining perfect stillness as he elevates a vivid, shiny, metallic yellow breastplate for the female's viewing. He holds this position momentarily before swiftly returning to an active display, concealing the breastplate again. A patch of blue, previously hidden, is revealed during the dance, appearing darker than the breastplate in certain angles. The alternating states of brightness and dynamic darkness remain distinct throughout the dance.

Red-Capped Manakins

The moonwalk display of the red-capped manakin (Ceratopipra mentalis) illustrates another instance of dynamic darkness and bright stasis used to attract mates. As he moves backward along a branch, he meticulously keeps his vibrant red head as motionless as possible while the darker parts of his body, especially the tail, vibrate.

It’s noteworthy that in nearly every example, males have evolved to present darker colors above brighter ones. This arrangement echoes the Thayer effect, where most animals exhibit brighter colors on their lower surfaces and darker colors on their upper surfaces. While Thayer’s effect has been associated with protective coloration, it likely stems more from mate selection preferences. The discussion of Thayer’s pattern is elaborated in the narrative "Painted By Nature," with a collection of visual examples available on the Pinterest page dedicated to the Thayer Effect.

The occurrence of this pattern in numerous courtship displays, which possess an explicit sexual purpose, supports the notion that it reflects a universal sensory bias favoring the contrasting mixtures of dark dynamic and bright static, particularly when an animal actively alters the visibility of its brighter and darker areas during a dance.

Marvelous spatuletail females favor purple atop the male's head while preferring green below. In the case of the Vogelkop superb bird-of-paradise, females opt for a combination of more black above with brighter blue below. Similarly, female red-capped manakins are attracted to males who lower their bright red heads beneath their darker body feathers. The three-spine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus), cassowaries (genus Casuarius), and turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo) showcase courtship colors with red below and blue above, while the mandrill’s ornate nose is also characterized by a blue upper section and red lower part, clearly indicating a sexual attribute.

Alongside the Thayer effect, numerous examples of explicitly sexual applications of the dynamic dark and bright static mixtures suggest that the broader pattern observable across animals cannot be adequately explained without considering a universal, nonadaptive, pre-existing sensory and cognitive bias.

Flame Bowerbirds

The flame bowerbird (Sericulus ardens) exemplifies dynamic darkness during his dance by lowering his flame-colored head in front of the black-tipped feathers of his wing. He repeatedly raises and lowers his head, flapping the dark feathers of his wing more rapidly and chaotically than the rest of his body, demonstrating a quicker downward motion compared to upward. Here, once more, female birds select mates based on the dynamic dark and static bright characteristics.

General Bird Coloration

The dynamic darkness effect can be observed in North American bird coloration as documented on the Audubon website. Numerous examples of this effect in birds and other animals are also featured on the Pinterest page Darker Extremities. The prevalence of this pattern is such that it is often easier to search for exceptions to gauge its occurrence. Out of a sample of 100 bird species, approximately 62% exhibit darker coloration at the wing tips compared to the lower breast, 32% share the same hue in both areas, and about 6% are lighter at the wing tips. The sampled bird list, including breast color and wing tip color, is presented in the final section of this article, with the brighter color italicized. Ignoring birds with no color variance, about 91% of the remaining 68 are darker at the wing tips than at the breast. Clearly, animals generally find this patterning more appealing than its inverse.

The bright-to-dark pattern extends to the rest of the body, where central areas like the breast, torso, and genital regions often appear brighter compared to outer areas such as the tips of bobbing head feathers, wings, and long tails. This is evident in species like the blue-footed booby (Sula nebouxii), which also displays darker wing coloration than its breast.

Rainbow Coloration in Birds

A psychological tendency favoring increased motion in colors at the purple end of the spectrum, decreased motion in colors towards the red end, and moderate motion in green should lead to the occasional emergence of a rainbow pattern across an animal's body, transitioning from red to orange, yellow, green, blue, and finally to purple and black from the central breast area extending over the shoulders and along the wings to their tips.

This specific color arrangement, or something similar, can be observed in various species, including the scarlet macaw (Ara macao), depicted above. While the long red tail feathers deviate from the darker extremity pattern, similar exceptions are noted across many bird species and butterflies, where darker patterns on the forewings’ edges are common compared to the hindwings. The tails in birds and hindwings in butterflies tend to be less dynamic than the wings, suggesting reduced mate selection pressure for dark colors in those regions. Various factors contribute to how animals perceive excitement in their potential mates, including proximity to reproductive organs, length versus roundness, and their orientation relative to the body, which will be explored in future discussions.

Rainbow coloration clearly serves as a sexual trait that has evolved primarily to engage the sensory systems of potential partners. This raises intriguing questions about how certain animals recognize and find amusement in colors arranged as seen in a rainbow, despite no formal teaching regarding the physics of visible light or the prism effect.

In the rainbow lorikeet (Trichoglossus moluccanus), the red breast transitions to orange and subsequently to yellow on the shoulder, which then shifts to green across much of the wing, concluding with a black wing tip. Other lorikeets maintain a similar pattern, displaying brighter coloration on the upper breast that gradually shifts to darker shades toward the wing tips, albeit with only some of the colors typically associated with rainbows present. The red-and-green (Ara chloropterus) macaws exhibit a similar gradient, showcasing an almost complete rainbow pattern from breast to wing tip.

The jandaya parakeet (Aratinga jandaya) displays a full spectrum of rainbow colors, starting from its red belly to the tips of its wings and tail, featuring an orange chest, yellow neck and head, green shoulders, and blue, purple, and black wing tips. From the perspective of a mate, the darkest and most dynamic parts are positioned above the brightest and most static ones. Similar patterns may also be evident in some individuals of the garnet-throated hummingbird (Lamprolaima rhami).

Bird Coloration by Taxa

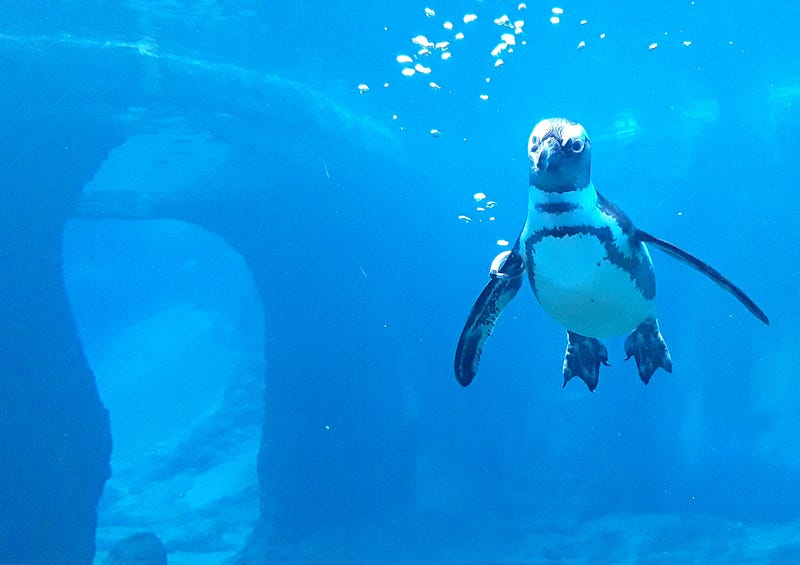

The prevalence of dynamic darkness can also be evaluated through different taxa. It is likely most common in species that have experienced less historical predation pressure or other ecological factors hindering mate selection advantages, and where beauty is more prominently observed. All living penguin species exhibit this pattern, except for the white-flippered penguin (Eudyptula minor albosignata), which has black wings with white edges. Similarly, all species of manakins (Pipridae) follow this coloration trend. Notable exceptions include ostriches, which possess pink legs and heads alongside white wing tips on a black body. These exceptions often relate to aggressive behaviors or warning coloration in various species.

Butterflies

Approximately 29 species of butterflies within the genus Morpho display dark coloration on their front wing tips. Similarly, most of the roughly 22 species in the genus Vanessa exhibit dark forewing tips with brighter colors on the remaining wing areas. Few exceptions arise within the swallowtail family, which encompasses at least 550 species. The monarch (Danaus plexippus) and genera Heliconius (longwings), Aglais (tortoiseshells), Antanartia (African admirals), Anartia (peacock butterflies), Greta (clearwings), and Atrophaneura (ruby swallowtails) serve as additional examples. A Pinterest page dedicated to butterflies showcases the tendency for darker extremities among them, although notable exceptions exist, such as the mourning cloak (Nymphalis antiopa) and the small blue (Cupido minimus), which have white outlines on their wings.

Butterflies often feature elongated, black, droplet-shaped extensions trailing behind them, resembling tails, likely satisfying a preference for dark, fluid shapes. This aligns with how animals universally associate motion and fluidity with excitement, alongside factors like brightness, length, and other qualities, as discussed in "More and Less Exciting Things and Categories of the Mind."

The evolution of dark outlines on butterfly wings to match a mate's preference for dynamic darkness assumes that the outer edges of the wings are more dynamic during movement compared to the inner sections. Darker colors are more frequently found at the tips of forewings than on hindwings, likely due to the forewings being more dynamic from a butterfly's perspective.

Mammals

Several notable mammalian examples of the dynamic darkness phenomenon include giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca), red pandas (Ailurus fulgens), koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus), Przewalski's wild Mongolian horse (Equus ferus przewalskii), tufted capuchins (Sapajus apella), golden-bellied capuchins (Sapajus xanthosternos), golden-backed uakaris (Cacajao melanocephalus), roloway monkeys (Cercopithecus roloway), blue monkeys (Cercopithecus mitis) with blue bodies and black limbs, mona monkeys (Cercopithecus mona), De Brazza’s monkeys (Cercopithecus neglectus), and the proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus) with blue arms and legs on a reddish torso. Bats (order Chiroptera) also exhibit brighter bodies paired with darker wings, akin to birds and butterflies.

Dark — Dynamic Bias

The concepts of dark dynamics and their counterpart bright stasis are observable throughout the animal realm, particularly in the coloration patterns and forms of numerous species, especially birds and butterflies. This pattern is so widespread that it poses challenges for explanation via popular natural and sexual selection theories.

A universal bias favoring the contradictory mixtures of dark dynamics and bright stasis over combinations of bright dynamics and dark stasis provides the simplest explanation. While how this bias is represented in the brain remains a mystery, it is clear that it does not evolve in tandem with male traits. If it did, male traits would exhibit far more randomness regarding configurations of darkness, brightness, stasis, and motion. No coevolutionary model of preference evolution can predict such a pattern, particularly given the overwhelming majority of species that seem to partake in it.

More and Less Excitement

The amount of light reaching the retina corresponds to levels of psychological excitement; more light equates to greater excitement, while less light leads to lower excitement, and no light (black) reflects zero stimulation. Thus, white is perceived as more exciting than black, though it should be noted that a black object typically reflects some light. Brains appear to categorize colors similarly, with redder hues interpreted as more exciting and bluer or purpler colors as less so, with green occupying an intermediate position.

Humans associate brightness, red, orange, and yellow with exhilarating experiences such as heat, anger, sexuality, emergencies, and danger, whereas darkness, blue, purple, and black relate to diminished excitement, often linked to feelings of sadness or lack of stimulation. Other animals clearly exhibit similar associations, connecting brighter colors to danger and sexual signaling, as evidenced by their roles in warning coloration and decoration of genital areas.

Light, brightness, and redder colors are likely associated with heightened excitement because they universally stimulate sensory systems and brains more effectively than their counterparts. Likewise, speed, motion, sudden movements, and other forms of dynamism likely induce greater stimulation in any animal's brain. A dark, rounded, motionless object tends to be minimally exciting and unfamiliar, potentially failing to attract positive attention. Conversely, a bright, elongated, rapidly moving object, while stimulating to the brain, may also be too overwhelming. Thus, animals may achieve a desirable balance by evolving paradoxical traits and behaviors where brightness is associated with slowness and darkness with speed.

Psychological Duality

Importantly, these preferences are not learned behaviors, as there are no external indicators suggesting that darkness is contrary to motion or brightness to stasis. It is easy to understand why animals might perceive these as opposites due to their contrasting effects on the brain, but this is not something observable in the natural world. The dualities of bright/static and dynamic/dark exist purely as psychological constructs, rather than as natural or observable binaries like bright/dark or fast/slow. This further supports the notion of their universal occurrence.

Random Bird Sample Data (For Reference)

In the following list, each random bird species is followed by the color of its breast and the ends of its wings, with the breast color listed first. The brighter color is italicized. The sample was generated by the website randomlists.com (2021), but any similar random bird list should yield comparable results:

Rainbow Lorikeet (red — black), Laughing Kookaburra (white — black), Ruddy Duck (black — black), Nicobar Pigeon (light blue — dark blue), Snowy Owl (white — mottled), Scaly-sided Merganser (white — black), Black-faced Dacnis (teal — dark blue), Grosbeak Starling (black — black), American Kestrel (white — black), Keel-billed Toucan (yellow — black), Black-faced Tanager (light blue — black), Bald Eagle (brown — brown), White-tailed Trogon (blue — black), Crested Wood Partridge (black — black), Augur Buzzard (white — black), Golden Conure (yellow — green), Palm Cockatoo (black — black), Ringed Teal (pink — red), Fairy Bluebird (black — black), Southern Bald Ibis (black — black), Golden-crested Mynah (black — black), Pied Imperial Pigeon (white — black), Curl-crested Aracari (yellow — black), Gouldian Finch (purple — green), Hadada Ibis (mottled — black), Green Woodhoopoe (green — dark blue), Indian Runner Duck (white — black), Military Macaw (green — green), Bearded Barbet (red — black), Red Bishop Weaver (black — mottled), Wattled Curassow (black — black), Harris’s Hawk (black — black), Steller’s Sea Eagle (black — black), Scarlet Ibis (pink — black), Crested Coua (red — black), Guira Cuckoo (tan — black), Malayan Great Argus (red — mottled), European Starling (mottled — mottled), Burrowing Owl (white — mottled), Green Aracari (yellow — black), Hyacinth Macaw (blue — blue), Javan Pond Heron (white — black), Palawan Peacock-pheasant (black — blue), Orange Bishop (black — black), Golden-breasted Starling (yellow — black), White-necked Raven (black — black), Sunbittern (white — mottled), Lanner Falcon (white — grey), Southern Ground Hornbill (black — black), Victoria Crowned Pigeon (purple — blue), Crested Oropendola (black — black), Grey-winged Trumpeter (blue — white), Meyer’s Parrot (green — yellow), Pekin Robin (red — grey), White-bellied Go-away-bird (white — black), Guam Kingfisher (pink — blue), Inca Dove (white — brown), Green Singing Finch (yellow — black), Melba Finch (mottled — brown), Sun Conure (orange — green), Yellow-naped Amazon (light green — dark green), Troupial (orange — black), Silver Gull (white — grey), Canary (yellow — black), Bridled White-eye (yellow — green), Eurasian Eagle-Owl (mottled — mottled), Cut-throat Finch (mottled — gray), Eastern Screech Owl (white — brown), Red-fronted Macaw (green — blue), Giant Cowbird (black — black), Rhinoceros Hornbill (black — black), Andean Condor (black — black), Palm Tanager (grey — black), Inca Tern (grey — grey), Blue-crowned Motmot (orange — green), Spangled Cotinga (blue — mottled), Scarlet-headed Blackbird (black — black), West Indian Whistling Duck (red — mottled), Boat-billed Heron (brown — white), Raggiana Bird-of-Paradise (red — red), Rosybill Pochard (black — grey), Roseate Spoonbill (white — pink), White-eared Catbird (yellow — green), Bali Mynah (white — black), Dhyal Thrush (white — black), Cattle Egret (white — white), Brazilian Tanager (red — black), Taveta Golden Weaver (yellow — mottled), Red-legged Honeycreeper (blue — black), Blue-fronted Amazon Parrot (green — black), Greater Roadrunner (white — mottled), White-crested Laughing Thrush (white — black), Yellow-hooded Blackbird (black — black), American Crow (black — black), Black Vulture (black — black), Hooded Merganser (white — black), Purple-throated Fruit Crow (black — black), Black-headed Gonolek (red — black), African Grey Parrot (white — black), African Penguin (white — black).

Works Cited

- McCoy, Dakota E., et al. “Structural absorption by barbule microstructures of super black bird of paradise feathers.” Nature Communications 9.1 (2018): 1–8.

- Random Lists. “Random Bird Species — List of Random Birds.” 2021. www.randomlists.com/birds.

- Parker, Dewitt Henry. The Principles of Aesthetics. United States, Silver, Burdett, 1920.