# Unveiling Lucy: Exploring Cultural Norms of Nudity and Shame

Written on

Chapter 1: The Discovery of Lucy

Fifty years ago, researchers uncovered a nearly intact skull and numerous bones belonging to a 3.2-million-year-old female of the Australopithecus afarensis species, often referred to as “the mother of us all.” Named “Lucy” after the Beatles' song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” her discovery sparked widespread fascination.

While Lucy has addressed several evolutionary questions, her physical appearance remains largely speculative. Common portrayals often depict her clad in thick reddish-brown fur, with various body parts visible amidst denser vegetation. However, recent advancements in genetic research suggest that Lucy may have been more exposed, if not completely naked.

Technological insights imply that our ancestors lost much of their body hair between 3 to 4 million years ago and did not adopt clothing until roughly 83,000 to 170,000 years ago. This indicates that for more than 2.5 million years, both early humans and their ancestors lived without clothing.

As a philosopher, my focus is on how contemporary culture shapes our understanding of historical figures. The representation of Lucy in media and academia may reflect more about our current societal norms than about her actual existence.

Section 1.1: From Nudity to Social Shame

The reduction of body hair in early human evolution likely arose from various factors, including thermoregulation, sexual attraction, and the need to combat parasites. Environmental and cultural influences may have also played a role in the eventual emergence of clothing.

Both the timing of body hair loss and the transition to clothing emphasize the significant energy demands of the human brain, which requires extensive care during the early stages of life. To cope with this, early humans may have formed pair bonds, fostering cooperation between partners in raising their offspring.

However, such partnerships come with challenges. Given our social nature, the temptation to stray from monogamy can complicate child-rearing. To maintain these social-sexual bonds, a sense of shame likely developed.

In the documentary “What’s the Problem with Nudity?” evolutionary anthropologist Daniel M.T. Fessler discusses the evolution of shame: “The human body is a supreme sexual advertisement… Nudity poses a risk to the foundational social contract, as it invites infidelity… Shame serves to promote fidelity and shared parenting responsibilities.”

Subsection 1.1.1: The Boundaries of Nakedness

Humans, often described as “naked apes,” are distinctive for their lack of body hair and their systematic use of clothing. The prohibition of nudity has created a reality wherein being unclothed is seen as a breach of social norms.

As civilization progressed, measures were likely implemented to uphold social contracts, involving punitive laws and social expectations, particularly regarding women. Thus, the connection between shame and human nudity emerged; being unclothed became synonymous with violating societal norms, leading to feelings of shame.

However, the definition of nudity varies by context. For instance, bare ankles once sparked scandal in Victorian England, while exposed torsos on Mediterranean beaches are commonplace today.

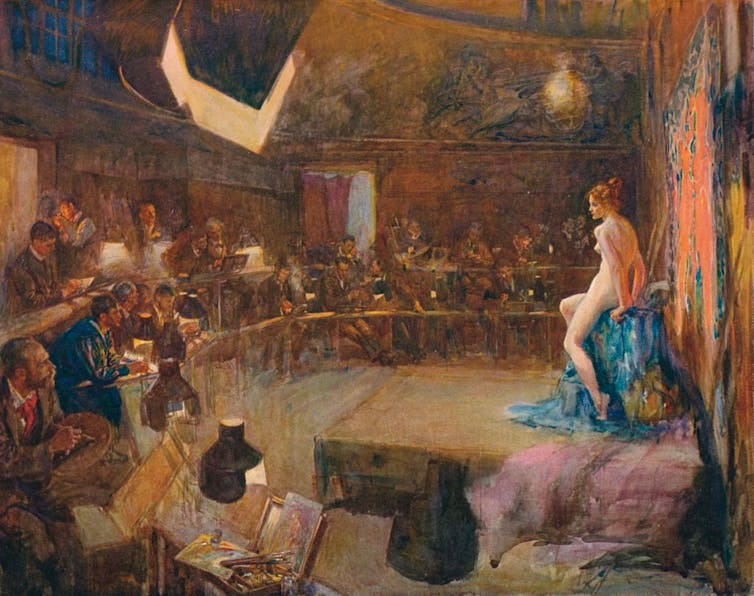

In discussions of nudity, art does not always mirror reality. Art critic John Berger distinguishes between nakedness—being oneself without clothes—and the “nude,” which objectifies the naked female form for male pleasure.

Chapter 2: Lucy's Cultural Representation

Feminist critiques, such as those by Ruth Barcan, challenge Berger’s delineation of nakedness and the nude, emphasizing that nakedness is shaped by cultural ideals. In her work “Nudity: A Cultural Anatomy,” Barcan argues that nakedness is not a neutral state but is imbued with meaning and expectations, often influenced by societal perceptions.

Nakedness can evoke a range of emotions, from intimacy and eroticism to vulnerability and shame. However, it is essential to recognize that nakedness exists within the framework of social and cultural norms.

Regardless of Lucy's hair coverage, she cannot be considered truly naked. Since her discovery, she has been illustrated in ways that echo historical notions of motherhood and family structures. Often, Lucy is shown accompanied by a male figure or children, her expressions reflecting idealized notions of maternal warmth and protectiveness.

This modern endeavor to visualize ancient ancestors has been critiqued as a form of “erotic fantasy science,” where researchers project contemporary beliefs about gender dynamics onto the past.

In their 2021 article “Visual Depictions of Our Evolutionary Past,” a diverse team of scholars undertook a different approach. They detailed their reconstruction of Lucy, highlighting the interplay between art and science and the choices made to fill in gaps in scientific understanding.

Their methodology contrasts sharply with other hominin reconstructions, which frequently lack empirical support and perpetuate misogynistic and racial biases. Historically, artistic representations of human evolution often culminate in images of a white European male, while female hominins are sometimes depicted with exaggerated features tied to harmful stereotypes.

One co-author of “Visual Depictions,” sculptor Gabriel Vinas, created a marble sculpture titled “Santa Lucia,” portraying Lucy as a nude figure draped in translucent fabric, symbolizing both the artist's uncertainties and Lucy's enigmatic appearance.

The veiled Lucy encapsulates the intricate relationships among nudity, clothing, sexuality, and shame. She is often idealized as a symbol of purity, yet I envision Lucy beyond these constraints—a figure unbound by societal expectations, perhaps even donning a Guerrilla Girls mask, embracing a more liberated identity.

This article is sourced from The Conversation, a nonprofit news organization dedicated to providing context for current events. To learn more or subscribe to their newsletter, visit their website.

Stacy Keltner has no affiliations with any organization that could benefit from this article, aside from her academic position.