The Hidden Costs of Mining: A Harsh Reality for Workers

Written on

Every circle of friends often has that one independent spirit, the one who shuns conformity and carves their own path, driven by an unquenchable thirst for new experiences and a fierce sense of freedom. This is a lifestyle that balances adventure with solitude, living on the edge of possibility.

In Argentina, while my peers were settling into the comfort of small-town life in Patagonia, one friend was looking beyond, captivated by the allure of distant lands. The prospect of swift riches and adventures abroad was irresistible. His sights were set on Australia, drawn by the popular "Fly-In Fly-Out" (FIFO) mining jobs that appealed to many young Millennials.

This role promised everything he desired: a chance to build a financial cushion for a more extraordinary life. Entry-level salaries began at $63,000 per year, while seasoned professionals could earn up to $113,000. To put this into perspective, I would take three years to match the entry-level salary he could earn in just one year in Australia.

The figures were not merely compelling—they were mesmerizing.

However, he was about to step into a realm that demanded resilience; 12-hour shifts in a structured environment, often in remote locations for stretches lasting anywhere from 8 days to an exhausting 12 weeks. It’s a stark contrast to ordinary life, characterized by seclusion, precious little sleep, and an ongoing struggle against the elements. When combined with a workplace culture as unyielding as the terrain, it’s no surprise that a significant portion of FIFO workers report elevated levels of psychological distress.

Our independent friend dismissed these warnings. With the confidence of youth, he was convinced he could overcome any obstacle. What could possibly deter a young man with iron resolve and physical strength?

Unbeknownst to him, the allure of FIFO was about to ensnare him tightly. In the relentless heat of the Australian Outback, even the strongest can be undone, regardless of their paycheck.

A Lone Wolf in the Desert

After enduring the application process, our friend successfully obtained a Working Holiday Visa (WHV) for a year in Australia. He arrived in Perth, secured a hostel, and sought a mining contractor position driving large trucks, his mind filled with dreams of wealth.

Australia, however, had other plans, and reality struck harder than expected. With 90% of "unskilled" jobs mandating full Australian work rights, his WHV relegated him to menial tasks—washing dishes and cleaning toilets. Yet even this lowly work was lucrative compared to his earnings back home: $25 an hour on a schedule of 7 days on, 7 nights on, and 7 days off, starting at 4 AM and ending at 6:30 PM.

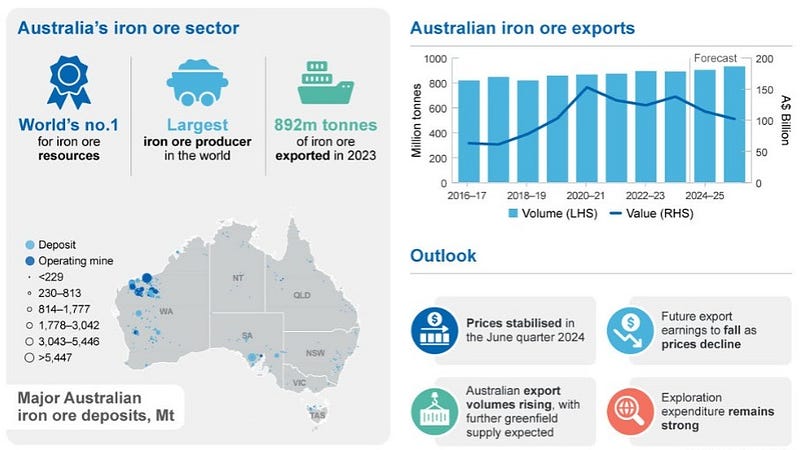

As he watched his meager savings dwindle away in a $250-a-week room, he longed for the wealth waiting in the mines. His target? The Pilbara region of Western Australia—a vast, arid expanse of red earth and blazing skies. Here, mile-long trains transport iron ore, Australia’s most valuable export, through the sweltering heat. From Perth, it’s a 17-hour drive or a $750 round-trip flight. Without a car, our friend, with light pockets and a heavy heart, took to the skies.

Eventually, he was working in the mines and earning a steady income. Yet, his ambition drove him to hustle for opportunities to improve his position. After five grueling rotations, he advanced from toilet cleaner to high-pressure washer, cleaning equipment vital to Australia’s economy. The pay increase to $34/hour on a 14:7 roster made the hard work seem worthwhile.

Yet, in this relentless environment, the initial excitement quickly faded. After each arduous 14-day stint battling the elements, he returned to civilization, his body yearning for rest. Two days of recovery barely eased his fatigue. The repetitive cycle wore him down. His legs, back, and neck ached, leaving him feeling exhausted. Yet, it wasn’t the physical labor that broke him.

It was the oppressive heat.

An Open-Air Furnace

Western Australia’s mining sector is the world’s largest supplier of iron ore, a $91 billion industry contributing about 13.6% to Australia’s GDP. It’s also one of the most punishing environments on Earth, where temperatures have reached an astonishing 50.7°C (123°F), a record for the Southern Hemisphere.

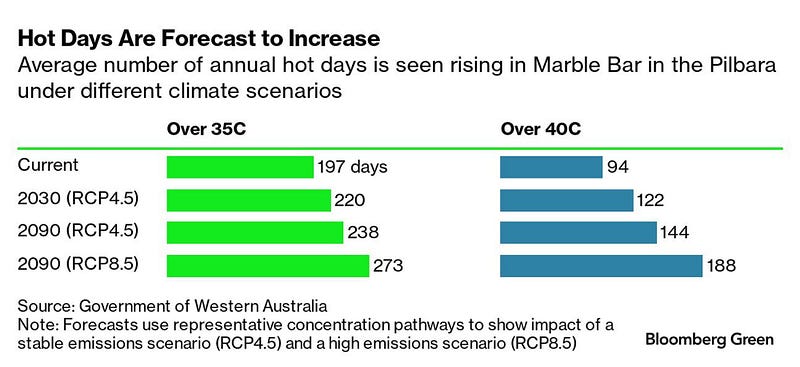

During the summer of 2023–2024, heat waves shattered records across the Pilbara. On December 30, Marble Bar recorded 49.3°C, its highest temperature in 122 years. That same day, the oppressive heat caused an iron ore rail line to buckle, leading to a train derailment. Thankfully, the crew was unharmed, but the railroad was shut down for four days.

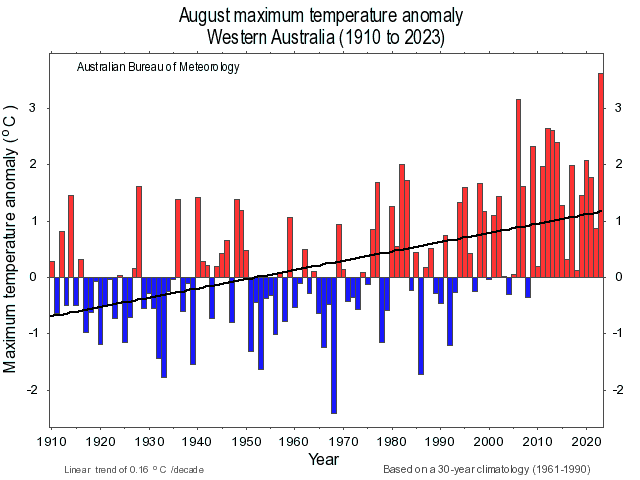

As if summer’s intensity wasn’t enough, Australia recorded its highest winter temperature on record—41.6°C at Yampi Sound on August 26, 2024—surpassing the previous record of 41.2°C set in 2020.

Sydney experienced its hottest mid-winter day since 1995, exceeding 30°C. With rising temperatures and snowfall amounts plummeting, winter itself seems to be losing its significance.

If this relentless heat can warp steel and derail trains, consider its devastating effect on the human body.

While we can adapt to rising average temperatures, extreme heat waves challenge our survival. These intense spikes push the boundaries of human tolerance, and when humidity is added, conditions can quickly become life-threatening.

When Heat Turns Deadly

A groundbreaking study in September 2024 tested human heat tolerance in extreme conditions.

In a climate chamber, Owen endured a sweltering 54°C with 26% humidity—equivalent to a wet-bulb temperature of 35°C, which is considered lethal after six hours.

Owen, a young, fit ultramarathon runner, was allowed unlimited water during the experiment. Researchers believed he was as heat-ready as possible.

But would that be enough for him to last 3 hours in such an environment?

The clock ticked. One hour… two hours… Suddenly, alarms blared. Owen’s muscles seized; he struggled to breathe. His core temperature soared towards the dangerous 39°C mark. At two and a half hours, he was pulled from the chamber.

> As Dr. Cheng, the study’s lead researcher, stated, “You’re producing as much sweat as you can, but it’s all evaporating. To cool down sufficiently, you need to sweat at a rate that is impossible, even for someone acclimated to heat. You max out.”

Another recent study within a heat chamber corroborated these findings, demonstrating just how grueling it can be to push human limits.

Imagine this hellish environment is not a controlled experiment, but rather the everyday reality for over 60,000 workers in expansive mines, plants, railroads, and ports. FIFO workers describe stepping outside as if they’re hitting a wall of heat.

The Heat Industry

Since 1900, extreme heat in Australia has claimed more lives than all other natural disasters combined.

Our lone wolf bore witness to this reality.

He was present in October 2017 when a 49-year-old technician employed by Rio Tinto—one of the largest mining companies in the world—collapsed and died while surveying potential drilling sites in the Pilbara. The man and his colleagues were required to trek over 16 kilometers daily in temperatures exceeding 37°C without proper stress assessments. It was a death march masquerading as employment.

What is the worth of a human life to corporate giants? A meager $80,000 fine for neglecting employee safety—a mere 0.00015% of the company’s $54 billion revenue.

Fast forward to today: measures such as cool zones near work sites, daily monitoring for high-risk tasks, and acclimatization periods for workers in extreme heat environments serve only as temporary fixes. Because let’s be honest: no amount of preparation can restore a life lost to the unforgiving Australian sun.

A study from Purdue University predicts that billions will face this lethal heat threshold as global warming progresses. Rio Tinto’s own projections suggest that days with temperatures above 40°C at their Pilbara operation may double to 80 annually by 2050. Ironically, this company emits as much carbon each year as Slovakia—equivalent to 7.1 million cars. BHP Group Ltd., the most valuable mining company globally, also anticipates that days over 40°C in eastern Pilbara could increase from 54 to 124 annually by the 2070s, all while releasing 380 million metric tons of CO? in 2023—nearly matching Australia’s entire output.

While these companies continue to exacerbate global warming, they are simultaneously calculating just how much more their workers will suffer in the inferno they’re creating.

The challenges faced by workers and the potential impact on billionaire investments in physical assets do not seem to deter the industry from its relentless expansion into some of the world’s most heat-stricken areas.

It’s not just Western Australian miners who confront this inferno. From the “Lithium Triangle” in northern Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia to the blistering US Gulf Coast and scorching conditions in India, millions of workers—from construction laborers to miners and hospitality staff—risk their lives daily in this dangerous game of extreme heat.

Welcome to Predatory Capitalism 101, where the relentless pursuit of profit is even hotter than the sun itself.

A Howling Present, A Scorching Future

The lone wolf is no longer alone.

After enduring fourteen demanding FIFO rotations—196 days in the harsh mining environment—he finally accumulated enough savings and energy to escape. Before the next grueling summer, he transitioned to a handyman position in Dunsborough—one of the most remote cities in the world—eventually securing permanent residency. A girlfriend and a dog followed, and he now enjoys a happy life south of Perth.

Despite his newfound happiness and more than seven years since he last visited Patagonia, the heat continues to escalate.

The industries that once employed him perpetuate carbon emissions that rival those of entire nations. They contribute to a conglomerate of powerful companies responsible for over a third of global emissions since 1965. These industries are not simply producing materials; they are fueling a future where the heat waves our lone wolf escaped will become a regular occurrence.

The same sectors that provide temporary stability are also driving a climate crisis that renders work conditions increasingly severe. This issue transcends personal experiences; it’s a global emergency.

FIFO life may seem appealing as a pragmatic financial decision, particularly for a Gen-Z generation grappling with a cost-of-living crisis while scrolling through endless content. However, this lifestyle is far from a mere escape; it conceals a more profound issue. The very industries that offer transient stability are simultaneously intensifying a climate crisis that makes such working conditions progressively perilous.

It’s not just about one individual finding peace after a taxing career; it’s about a systemic issue rendering extreme heat the new standard. The lone wolf’s departure is a personal triumph, yet it highlights a broader, more alarming trend: a climate in crisis driven by industrial forces. We must shift our perspective from merely adapting to surviving under intolerable conditions to questioning why we tolerate an industry that exacerbates the heat.

The critical question is whether we will continue to accept escalating heat as unavoidable or demand accountability from those who ignite the flames. How long can we overlook that our very survival may be jeopardized by the same systems that once promised prosperity? The furnace of climate change isn’t just looming on the horizon—it’s already upon us, and it’s time to confront who is truly intensifying the heat.

So, let your voice be heard.

Thank you for your attentive reading and support!

Subscribe for immediate insights and join the 900+ Antarctic Sapiens community for weekly content.