The Enigmatic Phenomenon of Spontaneous Human Combustion

Written on

The ancient world recognized four fundamental elements: air, water, earth, and fire. Among these, fire stands out due to its dual nature of destruction and renewal. Historically, fire has symbolized both death and purification, leading to a complex relationship marked by reverence and fear. Its transformative ability to chemically alter substances makes it an element of profound significance.

A captivating notion throughout history is the idea that fire can originate from within a person. In earlier beliefs, it was thought that fire was a component of the human body, capable of manifesting externally. This intriguing possibility has piqued human curiosity for centuries.

Tales of internal combustion have been chronicled throughout human history, blending folklore and reality. One of the most prominent examples involves spontaneous human combustion (SHC). Wikipedia defines SHC as:

“the pseudoscientific concept of the combustion of a living (or recently deceased) human body without an apparent external source of ignition.”

The stories of SHC have permeated various societal layers, from medieval legends to religious narratives, and even utilized as a rhetorical device by the Temperance Movement. This phenomenon is more than mere folklore; it has influenced perceptions and discussions surrounding mortality and science for generations. Despite advancements in modern science, the mystery of SHC remains a topic of debate. In this exploration, I intend to guide you through notable incidents of human combustion, its implications, and its relevancy in contemporary scientific discourse. These narratives, often dismissed as mere entertainment, have shaped historical perspectives significantly.

The Initial Documented SHC Case

While suggestions that the concept of human combustion dates back to ancient Rome exist, no Roman texts substantiate this claim. Instead, the first documented instance of spontaneous human combustion was recorded in the early Renaissance.

In 1654, Danish physician Thomas Bartholin described an incident in a Latin manuscript. Bartholin relayed a tale he had heard from his friend, physician Adolphus Vorstius, who had been told by his father. This story involved a knight from the reign of Queen Bona Sforza who allegedly vomited flames after consuming brandy and later died from the incident. Discrepancies about Queen Bona Sforza's identity complicate the narrative, but the tale has undeniably left an impression on the public.

This initial story sparked various retellings, evolving into folklore over time. The knight's name morphed into Polonus Vorstius, possibly a misinterpretation of Adolphus Vorstius, and details changed with each recounting, including the type of alcohol involved. This legend contributed significantly to the European fascination with SHC, linking it to excessive drinking and moral transgressions.

The prevalence of SHC narratives in Europe prior to the 20th century likely stems from societal attitudes towards sin and punishment. While many civilizations maintained robust medical documentation during the medieval period, it was mainly European cultures that produced combustion stories, likely due to their religious beliefs.

Subsequent SHC Accounts from the 1600s to 1700s

Documentation of SHC during the medieval and Renaissance eras often came after the fact, resulting in inconsistent details. Only a few physicians focused on compiling SHC narratives, leading to scarce and often contradictory information.

The French Corpse Explosion of 1644

In 1644, a letter from a physician in Lyon recorded a case of post-mortem SHC. Doctors examining a deceased woman's body were startled when her abdomen ignited from within, affecting her internal organs. This incident, attributed to excessive alcohol consumption or flammable medication, was likely caused by a gas explosion due to the use of lamps during autopsy.

British Noblemen’s Fiery Demise in 1653

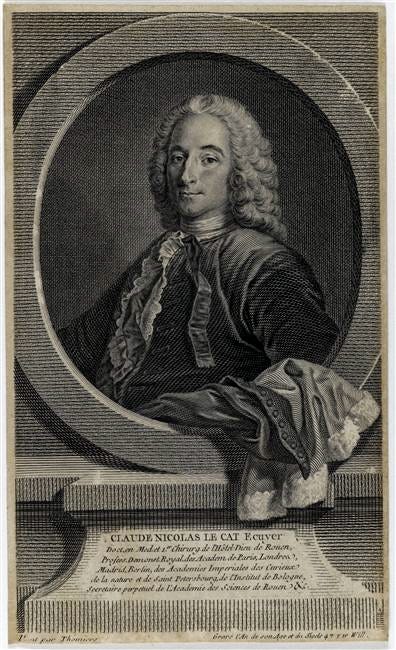

Reverend Giusseppe Bianchini's 1732 study featured various SHC accounts from the mid-1600s to early 1700s, coining the term spontaneous human combustion. He theorized that combustion resulted from an imbalance of gases in the stomach, often ignited by alcohol consumption. One notable tale involved three British noblemen who erupted in flames after drinking strong liquor, linking SHC to their excessive indulgence.

The Millet Trial of 1725

Perhaps the most influential case of SHC was that of Mrs. Nicole Millet in Rheims, France. Found incinerated in her chair, her body was almost entirely destroyed, with the chair remaining unscathed. Her husband, Jean Millet, was accused of murder, but his defense claimed spontaneous human combustion had occurred. This case marked a pivotal moment in the perception of SHC, transitioning it from folklore to a pseudo-scientific topic.

The Temperance Movement and Its Influence

The temperance movement emerged in the early 1800s, advocating for the reduction or elimination of alcohol consumption to combat societal issues. This movement merged medical science with folklore, linking alcohol to various ailments, including SHC. Propaganda often depicted alcohol as a poison, with fiery tales of SHC further strengthening their stance.

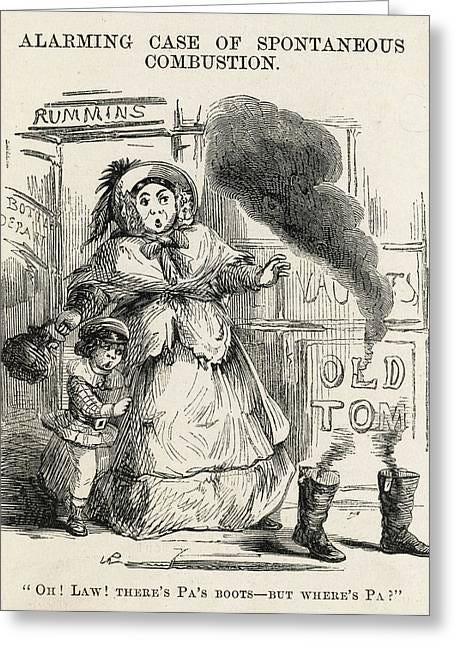

Publications and cartoons sensationalized the dangers of alcohol, with one article claiming that a man's blood could ignite due to excessive drinking. Notably, even Charles Dickens referenced SHC in his work, suggesting a belief in its validity. Although the temperance movement waned, the legacy of SHC narratives persisted, evolving through the years.

Famous Cases in Recent History

The tales of SHC continued into the 20th century, with notable cases emerging from the 1950s to the 70s, often supported by photographic evidence.

Mary Reeser — 1951

Mary Reeser became one of the most well-known victims of SHC, with photographic documentation of her remains. An elderly widow, she was found reduced to ashes in her armchair, with only her left foot remaining intact. The coroner attributed her death to accidental ignition from a cigarette, despite the implausibility of such a scenario given the extent of her cremation.

Beatrice Oczki — 1979

Beatrice Oczki's death followed a similar pattern, with her remains found as a pile of ash while her legs remained unharmed. Once again, the cause of her death was classified as an accident, leaving many unanswered questions.

Michael Faherty — 2010

In a rare modern case, 76-year-old Michael Faherty's death was officially ruled as spontaneous combustion by a coroner, marking a significant moment in the scientific discussion surrounding SHC. His body was found almost entirely cremated, with no evidence of foul play or accelerants.

Modern Theories and Explanations

Today, scientific inquiries into SHC have yielded various theories, with the wick effect gaining traction. This theory posits that a person's fat can act as a wick, allowing their clothing to burn like a candle once ignited. While studies have demonstrated this concept, it remains debated whether it applies to all historical accounts of SHC.

In conclusion, while some attribute SHC to supernatural forces, evidence increasingly supports explanations rooted in science. The phenomenon has evolved from folklore to a subject of medical inquiry, revealing how stories can shape cultural narratives across time.